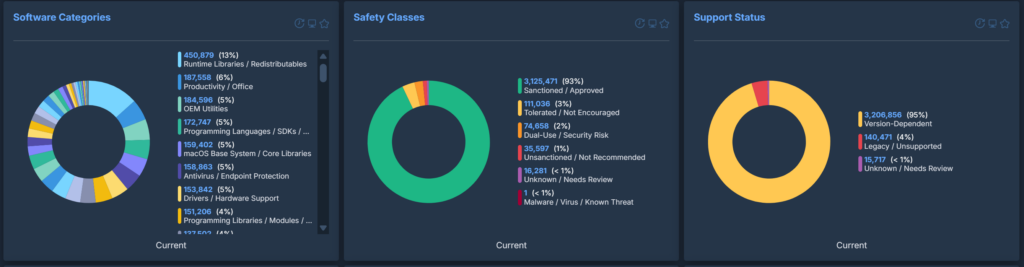

The software was categorised in three different ways:

- Software Purpose: What the software actually is/does

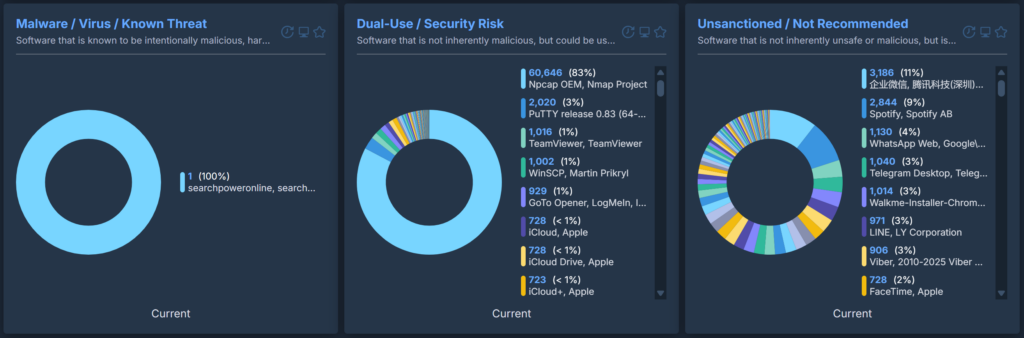

- Safety Class: Whether software is typically sanctioned/considered safe in organisations

- Support Status: Whether the software is known to be out of support or not

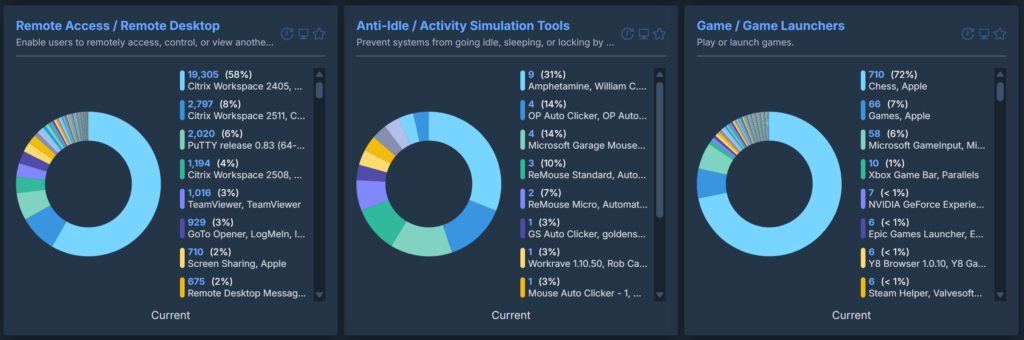

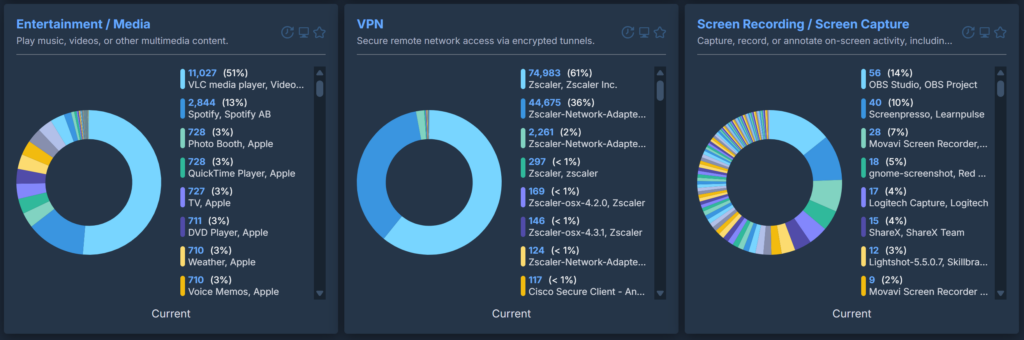

Software Purpose

These will sort an entire inventory into very clear categories and can easily highlight software of interest. If an organisation uses a single, standard VPN tool and this content reports dozens of different VPN tools installed across the estate, it is clear that users are installing their own. The same is true for remote access software, password vaults and so on.

Safety Class

Support Status

How we Created the Categorisation

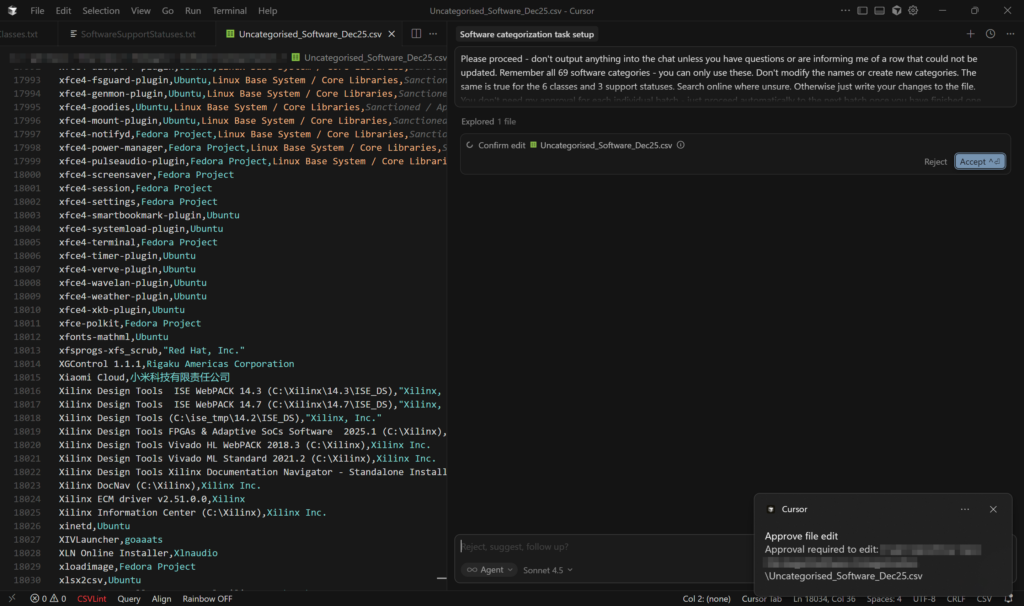

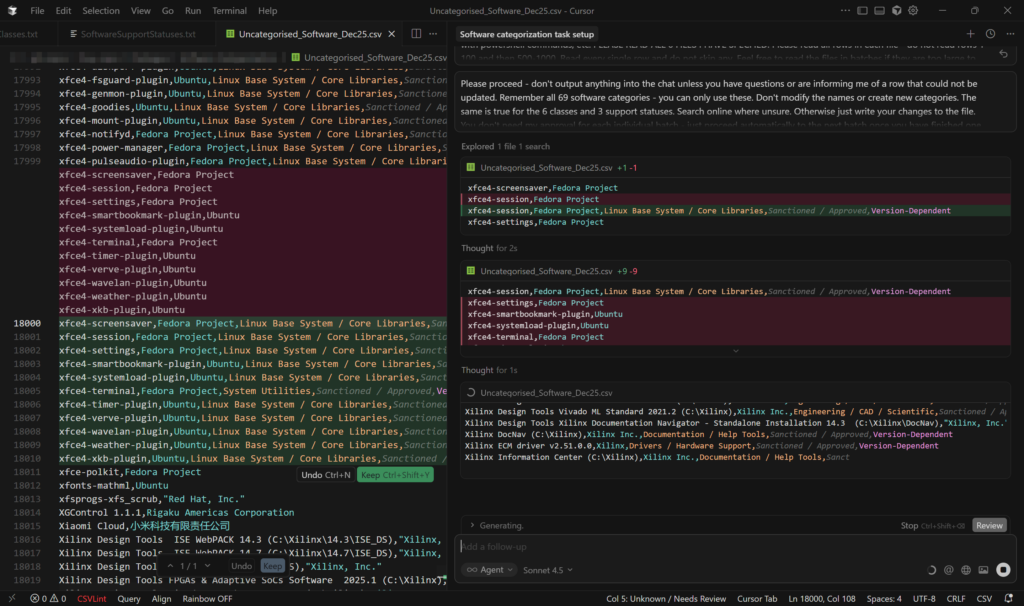

The mass-categorisations were done in Cursor with the Claude Sonnet model as opposed to in-browser with GPT-4. This model was far, far better at following specific rules for categorisation criteria and Cursor allowed it to edit the file itself and saved having to copy/paste results. It also allows files to be added as context, meaning the rules for the categories, classes and support statuses could each be saved in their own file and also no longer needed to be copied and pasted into a prompt window. This was also true of the example dataset along with a file of general rules for the categorisation that told the AI model what to do.

How we Deliver the Categorisation

What we Have Found so Far

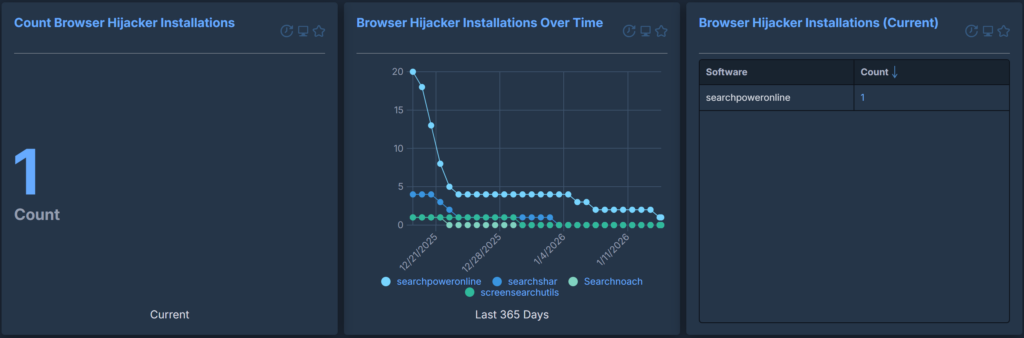

In practice, we have found that this content provides critical context when reviewing an organisation’s software inventory. It translates a faceless list of unknown tools into their purpose, how safe they are, and whether they are out of support or not. Individual categories/classes/support statuses can be extracted and monitored either as a report or visualised in a dashboard, allowing for a much-needed and comprehensive summary of what is actually in your environment and what you need to focus on